by Dr Carly Collier

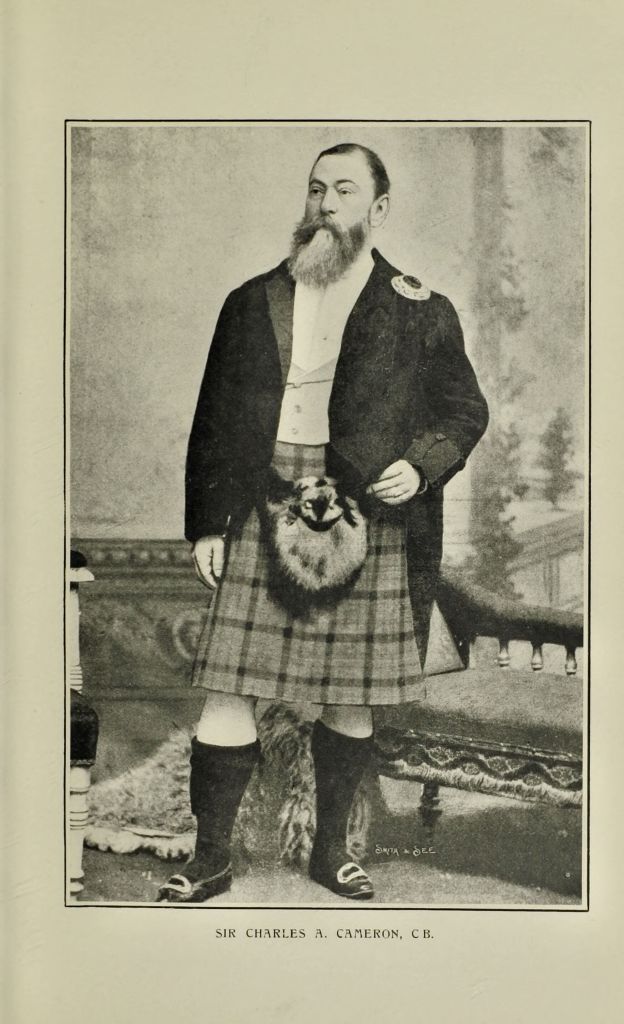

‘Does Dublin enjoy a pre-eminence in typhoid?’ asked an Evening Telegraph journalist in November 1891 of Sir Charles Cameron, Dublin’s esteemed Medical Superintendent Officer of Health.1 As a powerful local government official in a very public-facing role, Cameron was well-known in Dublin already, but as the Telegraph reflected, ‘[o]f late he has been more than ever prominently before the eyes of the citizens owing to the typhoid epidemic and the scare which has ensued upon the publication of particulars in reference to this dread visitation’.2 Things were particularly bad in Dublin in 1891, typhoid-wise. By the end of the year over 2,000 cases were thought to have occurred and just under 200 deaths attributed to the disease – which gave Dublin the third-highest death rate from typhoid of 49 large towns and districts in Britain and Ireland.3 The considerable local anxiety was understandable. However, Dublin Corporation struggled to contain more than just the disease at the time. They were also locked in an unfavourable public relations battle thanks to the suggestion that there was an especially high-profile victim of the epidemic – Prince George of Wales, grandson of Queen Victoria and then third in line to the British throne. The 26-year-old prince became unwell at Sandringham, Norfolk on 11th November and spent the next seven weeks being cared for by dedicated fever nurses and eminent physicians, including the infectious diseases expert William Broadbent.4

Though Prince George stayed at several different places in England and Ireland during the month before he fell ill, The British Medical Journal (BMJ) firmly pointed the finger at Dublin’s ‘insanitary fame’.5 Debate raged as to the probable cause. Was the vehicle for the disease sewage-contaminated oysters, perhaps, or could it be ascribed to Dublin’s lack of a main drainage system? The BMJ claimed that it was ‘no wonder enteric [typhoid] fever prevail[ed]’ in the city given ‘the great nuisance, the River Liffey, acting as an open sewer for Dublin, and saturating its soil with sewage’.6 Even more seriously, the purity of the city’s water supply was questioned. It was theorised that preventative works undertaken in the 1870s to prevent sewage contamination of the main reservoir supplying Dublin had been ‘hurriedly carried out’ and were no longer fit for purpose.7 The Corporation swung into damage limitation mode, announcing at the next council meeting that Charles Cameron (who was also Dublin’s Public Analyst) had tested the water and confirmed that it was ‘one of the purest, if not the purest, of the water supplies in the United Kingdom or in the world’.8 Moreover, the borough surveyor had checked the aforementioned preventative works of twenty years prior and found them sound. That, declared Dublin’s Lord Mayor, showed that ‘there was nothing in the water that should make anyone afraid to drink it’.9 The BMJ was also criticised for ‘attempting to bring discredit on [Dublin]’ by rehashing the old problem without any kind of investigation to prove its continued relevance.10 However, all this bad press clearly did not help Dublin’s contemporary reputation as the unhealthiest city in Great Britain and Ireland – and, in fact, as Charles Cameron admitted to the Evening Telegraph, typhoid’s bacterial cause – S. Typhi – was a persistent presence in Dublin in the decades around 1900.11

As part of the critically-acclaimed Typhoidland research and public engagement project, Typhoid, Cockles and Terrorism: How a Disease Shaped Modern Dublin has examined the turbulent history of the Irish capital city’s war against S. Typhi. The team behind Typhoidland have curated three major digital and physical exhibitions, each of which uses new research to explore the subject through different lenses – medical, sanitary, environmental, political and cultural. The exhibitions bring to life the everyday experiences of living and dying with typhoid in turn of the century Dublin, as well as interrogating the broader histories of Dublin’s sanitary infrastructure and bioweapons planning during the Irish War of Independence.

Fear & Fever: Living and Dying with Typhoid in Dublin is a physical exhibition at Royal College of Physicians of Ireland (both a virtual tour and a standalone digital version are available here and here) which draws on RCPI’s rich medical history collections. Photographs illustrating unimaginably difficult social conditions together with patient case histories, hospital records and material evidence of disease control measures reveal the lived experience of chronic illness and mass mortality c.1900 – and drive home the significant links between socio-economic inequalities and poor health. Fear & Fever also tells the story of the evolving science behind typhoid treatment and control through objects ranging from a decorative leech jar to an envelope with fumigation slits, a feeding cup for invalids, a stoneware water filter for (middle-class) domestic use and a milk bottle stamped ‘Tuberculin Tested’. Interviews contributed by public health and environmental science experts provide a contemporary perspective on how climate change, mass migration, crumbling infrastructure, and the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance are posing renewed challenges for Irish (and global) public health.

Our second exhibition, Stones & Bones: Containing Typhoid in ‘Dear, Dirty Dublin’ is an immersive, multimedia online exhibition created for Dublin City Library and Archive. Stones & Bones uses the important civic records held by Dublin City Archive to illuminate disease control efforts in the city c.1840-1940, and particularly its struggle with typhoid. Public health records, contemporary press responses, and photographic surveys demonstrate the authorities’ efforts to tackle typhoid during an era of surging urban growth and substantial inequality, as well as the limits of educational (behavioural) interventions. Stones & Bones also explores how imperial influences and one-size-fits-all thinking failed to provide solutions for Dublin’s sanitary crisis. Constructed between 1870 and 1906, Dublin’s London-inspired sewer system ended up impeding navigation in Dublin Bay and spreading typhoid amongst Dublin’s poor and working-classes by polluting local shellfish beds – and remains a problematic solution today in view of rising sea levels and climate change.

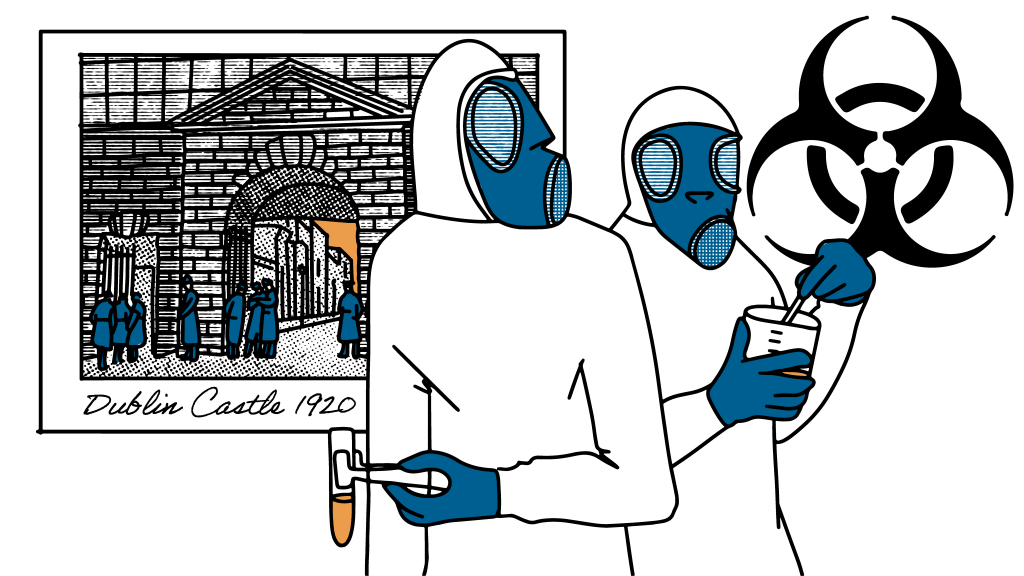

Finally, Contours of a Taboo: Bioweapons and the 1920 ‘Sinn Féin Typhoid Plot’ (with UCD Archives), an interactive virtual exhibition, surveys the history of bioweapons and the 1920 ‘Sinn Féin Typhoid Plot’, which saw senior IRA members consider infecting British troops with typhoid or glanders. Although the ‘plot’ was never executed, our historical research shows that use of bioagents against British troops was discussed on four separate occasions during the Irish War of Independence. Contours of a Taboo examines the evolving taboo surrounding the use of these weapons in the context of military planning, international governance frameworks, and science fiction.

All three exhibitions are hosted on Typhoidland’s digital portal here. Based on a map made by Charles Cameron in 1893 recording the geographical distribution of typhoid cases (in relation to soil types) over the previous decade, users can navigate around the city to explore a wealth of additional stories about the impact of typhoid on Dublin, its institutions and both famous and ordinary Dubliners. Further material available on the Dublin section of the Typhoidland website includes:

– Typhi’s Journey, a visualisation of the course of a human typhoid infection from the perspective of the microbe, S. Typhi, itself, set in the recognisable landscape of Dublin.

– Fear & Fever: 14 days of typhoid in Edwardian Dublin, a graphic novel which juxtaposes the story of fictional typhoid sufferer Teresa Byrne with an investigation into the outbreak of the disease carried out by Dublin’s real-life head of public health Charles Cameron. Fear & Fever draws on historical evidence to reconstruct the dynamics of typhoid transmission, public health politics and the personal experience of typhoid patients – and aims to contribute to redressing the class- and gender-imbalance of the historical record.

– Alive, Alive Oh and Antimicrobial Resistance Strikes Back, two new animations exploring, respectively, the link between Dublin’s unofficial daughter Molly Malone and typhoid, and the biological and social dynamics of AMR emergence, antibiotic dependency, and its dangers.

– Deadly Districts, a digital timeline which maps typhoid fever rates over sixty years in Dublin’s different registration districts – and shows that not all areas of the city were affected equally.

– and finally, (coming soon), a self-guided walking tour of central Dublin which will immerse participants in the city’s contagious past.

All of this content is fully-open access and available on the Typhoidland website, as well as the websites of our three key heritage partners – Dublin City Library and Archive, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Heritage Centre, and UCD Archives. Typhoid, Cockles and Terrorism: How a Disease Shaped Modern Dublin is a joint Irish Research Council/UK Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded digital humanities project led by University College Dublin and the University of Oxford.

The Typhoidland team are: Dr Claas Kirchhelle (INSERM; formerly University College Dublin), Dr Samantha Vanderslott (University of Oxford), Dr Carly Collier (University College Dublin) and Dr Emily Webster (Durham University).

Carly Collier, University College Dublin.

[1] ‘Our Saturday Interviews. No. 19 – Sir Charles Cameron’, Evening Telegraph (28 November 1891).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Charles Cameron, ‘Typhoid Fever and its Etiology’, in Report upon the state of public health and the sanitary work performed in Dublin during the year 1891 (Dublin: Joseph Dollard, 1892), pp. 705-37; Charles Cameron, ‘Typhoid Fever’, Report upon the State of Public Health and the Sanitary Work performed in Dublin during the year 1893 (Dublin: Joseph Dollard, 1894), pp. 27-37.

[4] Prince George recovered; he ascended the British throne in 1910 as King George V.

[5] ‘Typhoid Fever in Dublin’, British Medical Journal (21 November 1891), pp. 1113-4.

[7] ‘Typhoid Fever in Dublin’.

[8] ‘Typhoid Fever in Dublin’.

[9] ‘Ireland’, The Times (24 November 1891), p. 6.

[10] ‘Ireland’,

[11] ‘Ireland’,

[12] ‘Our Saturday Interviews’.