Dr Thierry Renaux

Aluminium is the most common metal of the Earth’s crust, but it does not exist in its native state. Three successive operations are necessary to obtain pure aluminium: the extraction of the ore, bauxite; the production of the alumina, or aluminium oxide, from this ore; and finally, the production of aluminium. This young metal was discovered in the middle of the 19th century. Until the end of this century and the development of an electrolytic process in 1886, it remained a rare and semi-precious metal.1Following this development, aluminium industries were set up in France, Switzerland, the United States and the United Kingdom.

This paper focuses on the second stage, alumina production, which generates almost as much residues as alumina, and more specifically on the refinery of Larne, Antrim Co., Ulster, owned by the British Aluminium Company (BACo). This paper lays the foundations for future research into the history of this plant, which started in 1895 and was the second to use the process patented by the Austro-Hungarian chemist Karl Josef Bayer in 1888.

Birth, Development and Decline of a Model Refinery (1894-1940)

The BACo was founded in 1894, to produce aluminium and the necessary raw materials in Great Britain.2 By 1897, BACo was a company with integrated operations. It differed from its late 19th century competitors in this respect, in that it had operations on both the upstream side (bauxite mines and alumina factory) and the downstream side (rolling mill and casthouse). The assets of BACo then comprised bauxite mines in Glenravel, a refinery in Larne, an aluminium smelter in Foyers (Scotland), a rolling mill and casthouse in Milton (Staffordshire), and an anode factory in Greenock (Scotland). Although based entirely in the UK on the eve of the 20th century, this industrial organisation was complex and spread over a vast geographical area. So, the alumina produced in Larne was shipped to Scotland by steamer and then to Foyers by train or via the Caledonian Canal.

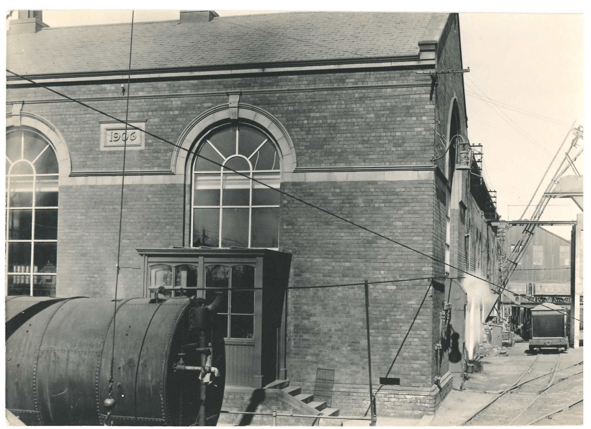

There were two main reasons for setting up a refinery at Larne. The first one was the presence of bauxite deposits in the vicinity of Ballymena, which had been known and exploited since the 1870s.3 The second reason was the existence of a port at Larne, the closest point to Great Britain. Harvey and McLaughlin from Belfast began construction of the factory in May 1895, with handover scheduled for mid-August the same year. The first production began on Christmas Day 1895, making Larne the second refinery to use the Bayer process after Gardanne in France (started in 1894). The start-up of the Larne plant, carried out by a team of English engineers and chemists and in collaboration with K. J. Bayer himself, was a long and laborious process. Major extension works were completed in 1898 (the refinery capacity almost doubled), in 1906, and then in 1910-11. By the eve of World War I, the Larne plant was the largest alumina refinery in Europe and its output of 15,000 tonnes per year covered virtually all the needs of BACo’s smelters. A few consignments were even shipped across the Atlantic.

© BACo Photo Collection, Larne Museum and Arts Centre

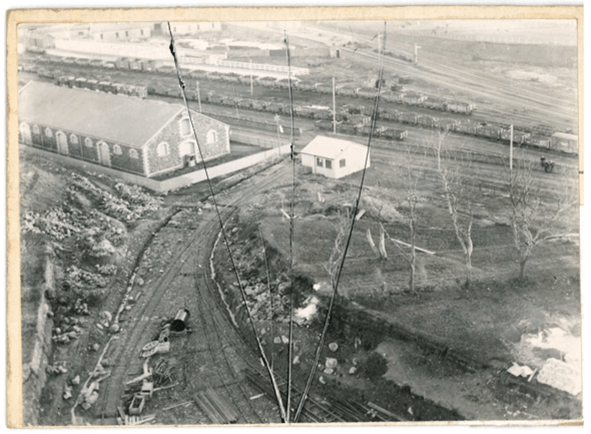

From a broader perspective, the Larne refinery played a key role in the industrial development of the Bayer process. And that influence was not limited to the first years alone. Several plants built from 1906 onwards – when the Bayer process came into the public domain – were fitted with equipment very similar to that used in Larne. The plant was yet reaching its limits, and BACo broadened its alumina strategy to include other facilities within the group. Firstly, from 1913 to 1919, BACo built a refinery at Burntisland (Fife Co., Scotland), more accessible from the new Kinlochleven smelter (built in 1905-09).4 Then, by the end of the 1930s, the extension of the Burntisland plant was completed, and a new refinery in Newport (Wales) was started. With this sweeping redistribution of alumina production across the UK, BACo management began to question the future of the Larne plant, which employed approximately 300 people at the height of its production.

© BACo Photo Collection, Larne Museum and Arts Centre

In 1894-95, BACo had the Antrim County bauxite extensively analysed. The objective was to source bauxite for the future refinery. However, the outlook was not very optimistic, and the company was also warned that it would probably be difficult to find satisfactory bauxite mines.5 Bayer considered it ‘more of a clay than a bauxite’ and expressed reservations about its feasibility.6 BACo quickly concluded that the Larne refinery was not performing at optimal levels.7 However, Irish bauxite remained a suitable raw material for producing aluminium sulphate.

Therefore, although BACo had acquired bauxite mines in Glenravel, it began searching for alternative sources of ore and first turned to France. From the start of the 20th century, it only used Irish bauxite in a blended form with French red bauxites. In 1902, BACo took control of the French company ‘Union des bauxites’ (in Marseille) and then used predominantly its bauxites. Explorations were also carried out in overseas regions (British Guyana and Gold Coast), where BACo created mining companies in 1927 and 1933. In some respects, the bauxite strategy pursued by BACo made the company a pioneer in this industry. Bauxite mining in Ireland declined quickly, as did all mining activity in the Antrim area, and (the consequences of the 1929 crisis further complicated the situation) ended completely in Ireland in 1934.

The War Effort: A Swan Song (1940-1944)

The Second World War changed things and brought a resurgence of activity and revitalised alumina production at Larne. Conflict-related constraints and strategies led the British government and BACo to join forces in the war effort. The industrial consequences were significant, especially – as regards aluminium and the related downstream production – in aircraft construction. Indeed, right from the first few months of the conflict, aircraft production became Britain’s largest industry, and the government took several steps to secure a stable supply of aluminium.

Shortly after Britain declared war on Germany, the Ministry of Supply took control of aluminium supplies and prices. In early 1940, the government funded a number of aluminium production and manufacturing facilities. To meet the strong demand for aluminium from the aeronautics and other war industries, orders for light metal were placed in Canada, the United States, Switzerland, and Norway.

In May 1940, to coordinate and optimise the construction of aircraft, Winston Churchill’s government created the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP). This ministry became essential a few months later when the Battle of Britain began, and it obtained priority access to raw materials for this sector over almost all the other types of munitions production. On 14 August 1940, control over aluminium, alumina, cryolite and silicon was transferred from the Ministry of Supply to the MAP, and a licence system was set up for the use of secondary aluminium. All primary aluminium was sold and distributed by the Ministry. Simultaneously, substantial quantities of secondary aluminium were produced by retrieving the aluminium from aircraft that crashed in combat and by sorting and melting manufacturers’ scrap. The effect was immediate: production of aircraft increased, and contributed to Britain’s victory. This massive-scale manufacture of aircraft triggered a significant and rapid increase in the production of aluminium and its raw materials: twice as much was produced in 1942 as in the previous year. However, most of Britain’s aluminium needs were met through imports, mainly from Canada. Following the closure of the last Irish bauxite mines in 1934, British aluminium production depended on ore imports from abroad, mainly from France. But with the start of hostilities and the fall of France, imports from the south of France stopped. New supply sources had to be considered, and by 1942, most of the imported bauxite came from the Gold Coast. In addition, maritime freight was hazardous. This prompted renewed interest in Irish bauxite, and in 1940, the British geologist Victor Ambrose Eyles was dispatched to Antrim to study its bauxite resources.8 Thus, he became the leading expert in the deposits of Northern Ireland, which he estimated at 750,000 tonnes. In the end, nearly 300,000 tonnes were extracted, a quite exceptional production entirely for UK consumption. Average monthly production during the war amounted to approximately 5,000 tonnes, whereas between 1877 and 1934 it had barely reached 600 tonnes: an eighth of that figure!

Reopening these mines meant restoring the infrastructure, and the optimal conditions were not reached until 1943. Special attention was also paid to the alumina factories: Newport was expanded, while minor changes were made in Burntisland and Larne. In Northern Ireland, aluminium was not the only industry contributing to the war effort. The shipyards of Belfast, Larne, and Derry were partially converted in order to manufacture weapons and military hardware.

The Dismantling of an Industry and its Heritage (1944-21st century)

In 1944, global aluminium output decreased by approximately 12%, mainly due to a drop in production in Canada, the USA and the UK. This meant there was less need for bauxite. Operations in Ireland peaked in 1943, with over 100,000 tonnes of ore mined, but declined sharply in 1944 and 1945. In August 1945, the MAP was abolished, and its activity transferred back to the Ministry of Supply, which decided in November 1945 to close the last bauxite mine, located in Templepatrick. In Larne, alumina production stopped in April 1947, resulting in the loss of 200 jobs (out of 260). Only a few workshops were kept in operation: from December 1948, they were used to produce red oxide pigment, extracted from the ‘sloblands’ where the residues from alumina production were stored.

© BACo Photo Collection, Larne Museum and Arts Centre

The reserves of mud were eventually depleted, and competition from other pigment sources led to a drop in demand in Larne. In 1957, BACo sold some of its land and buildings to the Corran Works Co. and on 1 July 1961, the factory, which employed 35 people, closed for good. The following year, the closure of the Milton rolling mill was announced. Two of BACo’s first factories had been closed down in the space of two years, closing a chapter in the history of aluminium in the UK. In the intervening period, in 1958, BACo had run into financial problems and been partially taken over by the American company Reynolds Metals – one of the six ‘majors’ of the industry of aluminium – in a partnership with the British firm Tube Investments. Since the start of operations at the Larne factory in 1895, approximately two million tonnes of red mud had been dumped in a pond – not without causing a nuisance for local residents. And yet this issue had been raised by James Sutherland, factory’s work manager, as early as 1896: ‘At present the red mud is useless, but experiments are being conducted, which it hoped will result in a profitable use being found for what would otherwise be a troublesome by-product.’9 A year after the alumina refinery closed, 150 tonnes of red oxide were produced each week using the slobland residues as a raw material. This oxide was used as a base for dyes, giving a rich red colour to products such as paint, tiles and linoleum.

© BACo Photo Collection, Larne Museum and Arts Centre

The red mud was initially extracted using a mechanical digger, which excavated everything within its reach from the shores of the lake. A barge called the ‘Mudlark’, fitted with its own dredging equipment, was then deployed. The liquid red mud was pumped to the plant via pipes from the barge’s on-board tanks. The mud was then desilted, filtered and dried before being packaged and shipped to the Red Oxide Group in Wick, near Bristol England. The mud that was unsuitable for use in red oxide production was sold to the Magheramorne Cement Works. This reuse raises questions, given that plants of this type everywhere else, yesterday and today, still do not know what to do with these residues.

Once the factory had closed and the slobland had been completely dredged, BACo’s land and buildings were sold. In the early 21st century, a red-brick building on Curran Road was one of the few remaining heritage assets bearing witness to one of Larne’s historical industrial activities. The sloblands have been rehabilitated and now house a bowling green, a children’s playground and a caravan park. A few place names, such as Redlands Road, still pay tribute to this industry. Sadly, awareness of Northern Ireland’s industrial heritage came too recently for the BACo factory to benefit from conservation measures.

Traces of bauxite mining are less scarce. A few spoil heaps and industrial heritage assets survive to this day, but most are hidden or have even been swallowed up by vegetation. Thus, at the start of the 21st century, only a few traces remained of the industry dedicated to ‘fairy metal’ – an expression still used in Larne to refer to aluminium.

- The discovery was made simultaneously and independently by a Frenchman, Paul Héroult, and an American, Charles Martin Hall. ↩︎

- ‘Organisation of the Aluminium Industry in Great Britain’ [for Manchester Guardian Commercial] (22 May 1936) (BACo Archives, University of Glasgow Documents 347/21/40/15). ↩︎

- Until the 1890s, this bauxite was used for chemical and refractory applications. ↩︎

- Andrew Perchard, Aluminiumville: Government, Global Business and the Scottish Highlands (Lancaster: Crucible Books, 2012). ↩︎

- Benjamin E. R. Newlands, ‘Report on the Deposits of Bauxite in County of Antrim, Ireland’, 21 March 1894 (BACo Archives, University of Glasgow Documents 347 21/34/6/9). ↩︎

- Paul Soudan, Historique technique et économique de la fabrication de l’alumine, (Paris: Groupe Pechiney, 1970), p. 41. ↩︎

- Arthur Lodin, ‘La métallurgie. La grosse métallurgie à l’Exposition de 1900 (suite)’ in Le moniteur du Docteur Quesneville…, 4e série, t. 18, 1re partie, Livraison 750 (June 1904), pp. 444-51. ↩︎

- Victor Ambrose Eyles, Report on the Bauxite Deposits of Northern Ireland for the Non-Ferrous Metallic Ores Committee of the Ministry of Supply (November 1940). ↩︎

- James Sutherland, ‘Description of the Alumina Factory at Larne Harbour’, Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Proceedings, 3-4, (1896), pp. 380-89. ↩︎