by Dr Mauve Carbonell

In the early 1970s, driven by an overall increase in needs for raw materials – aluminium in particular – the Alcan company established an alumina production plant in Aughinish near Limerick.[1] But why build a plant costing several hundred million pounds in the middle of the Irish countryside, in Aughinish, on the Shannon estuary? The mystery deepens when we consider that the Republic of Ireland lacked raw materials (good-quality bauxite, sodium hydroxide, abundant and cheap energy), outlets (a smelter), expertise in this field or even a highly developed industrial sector. But in the context of an increasingly international aluminium industry and the enlargement of the European Economic Community (EEC) – with the accession of Ireland, the United Kingdom and Denmark in 1973 – setting up an alumina production plant on the west coast of Ireland was not as absurd as it might have seemed.

Alumina is the intermediate material used to produce aluminium. Extracted from bauxite using the Bayer process, the alumina industry developed in parallel with the aluminium industry since the end of the 19th century. The alumina industry is a heavy chemical industry, which uses high-temperature sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in its manufacturing process and generates large quantities of industrial waste. Companies like Alcan (Aluminium Canadian Company) dominated the aluminium sector in the late–20th century along with Alcoa, Reynolds, Kaiser in the USA, French company Pechiney and Swiss company Alusuisse. This industrial sector, whose origins were in Europe and North America, became globalised. The original companies have since become multinationals; many have been absorbed by even larger groups through mergers and takeovers. [2]

An Industrial Success Made Possible by the Irish Authorities

The plant project was conceived by Alcan as a vital link in a global economy: importing bauxite from Guinea and exporting the alumina to European smelters to produce aluminium. An alumina refinery in Ireland would supply the smelter that the Canadian company was on the point of completing in Lynemouth (Northumberland) with an annual capacity of 130,000 tonnes, requiring 260,000 tonnes of alumina per year.[3] Other main criteria were: the possibility of a deep-water port in order to import bauxite on 65,000-tonne ships; a site to store the residues; available manpower; access to the Common Market; and attractive financial conditions for constructing and operating the plant. With regard to this last point, the action of the Irish state and the regional authorities was a determining factor in the decision to locate the plant in County Limerick.[4]

At that time, Ireland lagged behind its European neighbours in economic terms, due to low growth and high emigration. After having pursued a protectionist policy since independence in 1922, Ireland adopted an open economic policy in the post-war years to attract foreign capital and multinationals and develop exports. This policy would be accentuated with accession to the Common Market.[5] The prevailing view was that foreign investment, particularly from North America, and an export economy would drive the country’s economic growth and development, enabling it to catch up.

The national and regional authorities saw the project proposed by Alcan as an unprecedented development opportunity. In their view, it was a matter of developing the industrial sector, particularly in the outlying and rural areas of the west of the country which were suffering the most from emigration and unemployment, while taking pressure off the Dublin region, which, by contrast, had become attractive.[6] Some members of Limerick County Council believed that this project could even change the course of history, commenting that: ‘In the twenty-five-year period from 1946 to 1971, County Limerick […] lost over ten thousand people […] a loss of almost 11%. […] It is obvious that industrial expansion is needed to halt this constant drain of population’.[7]

The Irish authorities’ support for ‘Ireland’s biggest-ever private investment’ took the form of direct subsidies, tax exemptions, grants for training costs, improvements to the road network, water supplied by County Limerick, grants for housing construction on the basis of a plant project with an estimated construction cost of £50 million, creating 800 permanent jobs and producing 800,000 tonnes of alumina per year. Subsidies increased in proportion to the cost of the project which soared: in 1983 it was estimated at more than £630 million, compared with £267 million in 1977 and £57 million in 1971.[8]

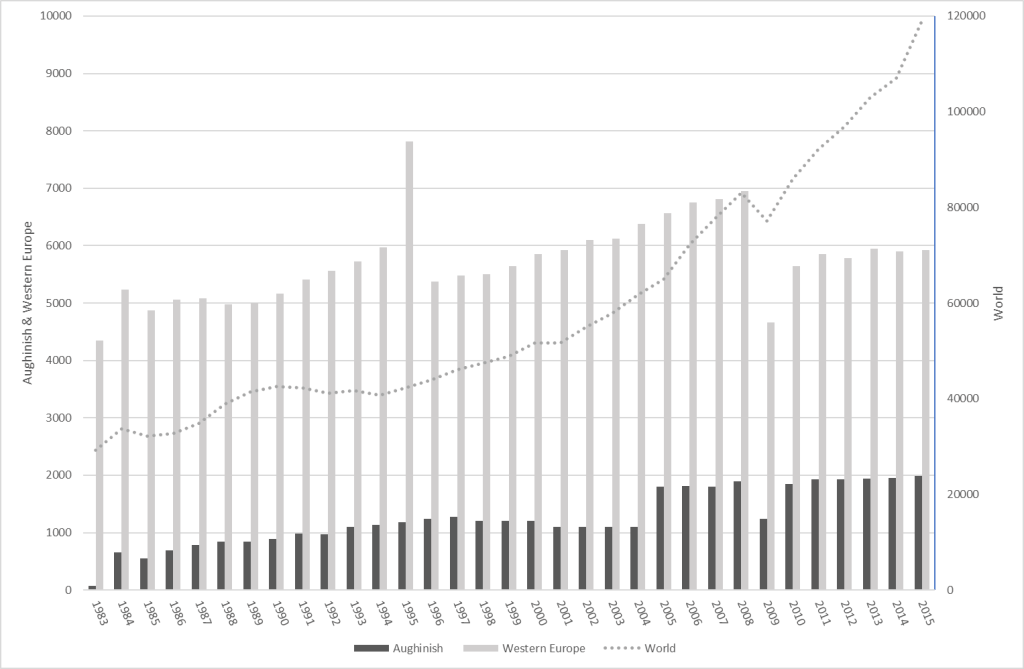

Launched in 1971, the project was slowed down by that decade’s oil crises. The plant’s construction site was officially inaugurated seven years later, on 9 June 1978, in the presence of Taoiseach Jack Lynch, who was already in office when the first discussions took place between Alcan and the Irish government in the late 1960s.[9] On 4 September 1983, the first tonnes of alumina were produced by Aughinish Alumina Limited (AAL), a partnership Alcan (40%), Billiton (35%) and Anaconda (25%). The plant did not reach full production capacity in the first few years, due to the low price of aluminium. The alumina industry depends upon aluminium as its main, or even only market outlet, and this was the case at Aughinish. Demand for aluminium did not increase significantly again until 1987. In 1989, the production capacity of the Aughinish refinery rose to 900,000 tonnes. The data show that production increased steadily, with a few periods of stagnation (collapse of the USSR in 1991) and sharp decline (economic and financial crisis of 2008). In the 2010s, the plant’s production capacity reached two million tonnes.

Sources: U.S. Geological Survey, Minerals Yearbook, ‘Bauxite and Alumina’, 1983-2016 (data for Ireland); The International Aluminium Institute (www.world-aluminium.org) and U.S. Geological Survey, Historical Statistics for Mineral and Material Commodities in the United States, ‘Bauxite and Alumina’ (data for Western Europe and the world).

AAL was Europe’s largest alumina producer and its share of Western European alumina production grew steadily, reaching almost 35% in the late 2010s. Its production capacity increased while, in parallel, older generations of plants that were considered obsolete, too small or poorly located were shut down. Having become the sole owner in 1995, Alcan sold in 1999 the plant to the Swiss group Glencore. In 2007, the Rusal-Sual-Glencore merger, which led to the creation of Rusal, a new giant in the aluminium industry seeking raw materials for its smelters, brought the Irish plant under Russian ownership.

Environmental Controversies Surrounding Alumina Production at Aughinish

The Aughinish refinery is an industrial success, but, like other alumina refineries, it has not escaped environmental controversies, several of which punctuate the history of the plant.[10] In the 1970s, when the project was launched, the issue of its environmental impact was raised during discussions within County Limerick Council. Members of the council expressed various concerns: ‘effect, if any, on agricultural land and farm stock’; ‘aggravate the position in relation to a cattle disease peculiar to the district’; ‘the discharge from the decant pond in an exceptionally wet year’; ‘on pollution of the Shannon water’; ‘on the toxicity of the red mud and the height of the chimney stacks’; ‘on noise level’.[11] Environmental regulation was still in its infancy in Ireland and the instrument available to local authorities – the granting of planning permission – was not very effective, given their limited resources.[12]

In the eyes of the County Council, everything had hence been done to limit the environmental risks. Assurances had been obtained from the company, and the State, through its various organisations, had approved the project. The planning permission granted was nevertheless accompanied by a list of some twenty conditions regarding ‘controls in air and water pollution, the accumulation of red mud, spillages, disposal of effluents and monitoring’, which were deemed sufficient to prevent any harm to the environment.[13] Moreover, these risks were systematically put into the perspective of the unprecedented economic impact expected for the region.

But in the 1980s, the first accusations appeared: storms of bauxite dust and residues turned the surrounding area red, and, worse,farmers from around started reporting to have problems with health animals. In the early 1990s the controversy grew into a government issue involving NGOs, local residents and farmers.[14] In 1995, the Askeaton/Ballysteen Animal Health Committee complained to the AAL that red dust was contaminating the area around the plant, and Greenpeace Ireland asked AAL to investigate the composition of the effluents discharged from the plant.[15] The farmers stepped up their complaints and accused AAL of polluting their farms, an accusation which the company formally denied. The first complaint was lodged by Liam Somers, a cattle farmer in Issane, Ballysteen, who counted overs 90 cattle death between 1990 and 1995 according to figures quoted in the national press.[16] This unusual situation at Liam Somers’ farm, and the similar one reported by Justin Ryan, another cattle farmer in Toomdeel (31 dead cattle in 1995), along with public hearings at which the farmers expressed their discontent, attracted media attention and forced the authorities to react. In a broader context of disputes related to environmental concerns, the government’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), newly established under the Environmental Protection Agency Act, 1992, took up the issue. In 1995 the EPA launched an investigation into the causes of ‘serious animal health problems’.[17]

The investigation lasted several years and covered 25 identified farms. When the results of the investigation were published in 2001, they cleared the local industrial players (AAL but also the Money Point and Tarbert power plants, and the Wyeth baby food factory) of any role in these mysterious cattle deaths. Instead, the report pointed to poor farming practices. The report reached similar conclusions for all the farms concerned, making the claimants very angry. The farmers still question this report today and distrust the role of the State, accusing it of favouring industry at their expense. They have renamed the EPA the ‘IPA’, for ‘Industry Protection Agency’.[18]

The case of the Askeaton farmers attracted extensive media coverage and involved many players, both local (farmers, Askeaton/Ballysteen Animal Health Committee) and national, including the Irish Farmers’ Association and a number of environmental protection organisations (Greenpeace, Cork Environmental Alliance), over a period of several years. It illustrates the history of environmental disputes regarding alumina plants, and caused lasting damage to AAL’s image at a local level. In more recent times, such disputes concerning AAL have focused on ‘red mud’, the residue generated during bauxite processing, and how it is stored. For example, allegations concerning contamination of soils and the Shannon estuary through infiltration and rainwater runoff, as well as instances of airborne toxic dust, were made when the plant submitted an application to extend its bauxite residue disposal area.[19]

In the face of environmental disputes, Alcan and its successors have made a number of technical developments (improving storage pond watertightness, reducing emissions, recovering toxic substances from effluents, etc.) and yet they have still not managed to find a commercial outlet through which to “recover” red sludge, or to repair the tarnished image of a chemical industry that cannot be trusted.

[1] Bradford Barham, Stephen G. Bunker and Denis O’Hearn (eds), States, Firms, and Raw Materials: The World Economy and Ecology of Aluminium (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994).

[2] Duncan Campbell, Global Mission: The Story of Alcan,Vol. 3 (Montréal: Ontario Publishing Co., 1991).

[3] Ludovic Cailluet, ‘The British Aluminium Industry, 1945-80s: Chronicles of a Death Foretold’, Accounting, Business and Financial History, 11:1 (2001), pp. 79-97; Alcan Aluminium Limited, Annual Report 1972.

[4] Industrial Development Authority (IDA), Shannon Free Airport Development Company (SFADCo) and County Limerick.

[5] Gerard McCann, Ireland’s Economic History. Crisis and Development in the North and South (London: Pluto Press, 2011); Andy Bielenberg and Raymond Ryan, An Economic History of Ireland since Independence (London: Routledge, 2013).

[6] Anthony Foley and Dermot McAleese (eds), Overseas Industry in Ireland (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1991), p. 154. Cf. also National Economic and Social Council, Regional Policy in Ireland: A Review, 1975.

[7] Limerick County Archives/LK/MIN39/LCC, Meeting of the Limerick County Council, 8 April 1974.

[8] Irish Independent (10 June 1978).

[9] Irish Independent (10June 1978).

[10] Mauve Carbonell, ‘Environnement et Usines d’Alumine: Des Plaintes des Riverains à la Contestation Globale des Boues Rouges, les Exemples de Gardanne, France et d’Aughinish, Irlande, XXe-XXIe siècles’, Cahiers d’Histoire de l’Aluminium, 67 (2021), pp. 74-93

[11] Limerick County Archives/LK/MIN/39, Deputy Noonan, Councillor Barrett, Senator O’Brien, Councillor Daly, Councillor Dwyer, Meeting of Limerick County Council, 8 April 1974.

[12] George Taylor, Conserving the Emerald Tiger: The Politics of Environmental Regulation in Ireland (Dublin: Arlen House, 2001), p. 19.

[13] Irish Independent (11 April 1974).

[14] Interview with Liam Flemming of Adare, County Limerick (13 June 2019).

[15] Integrated Pollution Control Licence 35, EPA Inspectors Report, 10 Feb. 1997, p. 11. https://www.epa.ie/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

[16] Irish Independent (17 January 1995).

[17] Department of Agriculture, Food and Rural Development, EPA, Investigations of Animal Health Problems at Askeaton, County Limerick, Main report, 2001. https://www.epa.ie/. Accessed 13 May 2022.

[18] Interview with Pat Geoghean of Glin, County Limerick, 25 June 2019.

[19] Irish Times (7 February 2022); Limerick Post (17 February 2022).