By Dr Anne Mac Lellan

As certain nebulae are resolved into stars by powerful telescopes, so specific chest sounds, obscure from their lowness, may be determined by the double stethoscope.1

Arthur Leared, 1856.

The Great Exhibition, held in London’s Crystal Palace in 1851, displayed the wonderful, the beautiful, the useful and the bizarre inventions of industry, technology and science to a marvelling public. It showcased the ‘works of industry of all nations’ and comprised items produced in the United Kingdom (which included Ireland), British colonies and dependencies, and Foreign States. It catered for all tastes, and if a visitor felt unenthused about raw materials, industry and technology, then (s)he could marvel at the more ancient treasures on display, such as the Koh-i-Noor diamond, mined in India and controversially shipped to Britain in 1849, as well as the recently discovered Irish Tara brooch, a silver brooch with gold filigree depicting animals and abstract shapes, regarded as one of the finest products of Ireland medieval metal workers.2

Exhibits were broken down into classes with Class X containing some 751 entries pertaining to philosophical, musical, horological and surgical instruments. Entry number 620 in Class X read simply: ‘Leared, Arthur, Oulart, Wexford, Ireland – Inventor. Double stethoscope, made of gutta-percha.’ There was no accompanying illustration.

The stethoscope from Wexford was largely ignored by the medical establishment and the media and failed to attract any interest from commercial companies. Arthur Leared, its inventor, did not win a prize or a medal; however the mere fact of exhibiting it was to prove extremely important to him in later years. The two simple sentences in the catalogue were to allow him to establish precedence in the design of the bi-aural stethoscope. At the time, regardless of lack of commercial opportunities, it must have been extremely exciting, and a matter of pride, for a young Irish doctor, in his late 20s, to have displayed an exhibit in such a prestigious exhibition of unprecedented scale and grandeur, housed in the purpose-built crystal palace in Hyde Park.

In 1816, French doctor René Laennec developed a mono-aural stethoscope that allowed him to listen, with one ear, to a woman’s heart without impinging on her modesty. It also magnified the sound of her heart, essential in a woman whose body fat rendered these difficult to hear. However, the stethoscope and the symptoms that it revealed were hotly debated for at least two decades in medical journals and societies, with many doctors sceptical of its value. The variety of chest and heart sounds audible through stethoscopes and technical difficulties in hearing and identifying these crackles, murmurs, whooshings, swishings and beats and relating them to the new complex rhetoric and descriptions led some to reject the stethoscope.3

Laennec stethoscope of 1819. Wellcome Collection.

By the time of the Great Exhibition, the mono-aural stethoscope, usually in the form of a wooden cylinder with a flared end, had become part and parcel of the professional medical man’s kit, often stowed in his hatband for convenience. Joel Reiser’s masterly essay on the stethoscope’s transformation of medicine argues that the instrument was the beginning of the end of the primacy of the patient narrative in the elucidation of disease symptoms. The advent of the stethoscope meant that symptoms that were imperceptible to the patient were now audible by the physician.4 This represented a profound change for physicians’ perception of illness.5 Foucault in the Birth of the Clinic regarded the changes brought about by the French school of medicine, in particular pathological anatomy and the stethoscope, as the most important transformation in the history of Western medicine.6

So, why did a young Irish doctor decide to re-design this influential instrument? Leared had trained at Trinity College (Dublin), and later, in the Meath Hospital, also in Dublin, by exciting, innovative teachers including Professor William Stokes, who had written extensively on the stethoscope. Leared may have been inspired by example to test out new ideas and to invent or modify new instruments. Dublin was a hub of medical innovation; the mid-19th century was Irish medicine’s so-called gold era.7

The single rigid stethoscope was good but not ideal; listening through one ear only did not provide the quality of sound that could, presumably, be heard by using both ears together. External sounds were not excluded, and could confuse, as one ear was attuned to the environment rather than the patient’s body. In fact, the idea of a double stethoscope was not new, having been previously mooted in the 1820s but the flexible materials required to make the tubes were not available. Now, some three decades later, suitable materials were available. Leard used gutta percha, a form of natural latex. This flexible material which was newly imported into Europe was extracted from eight species of trees from a geographical area including Malaya, Cambodia and Sumatra. Gutta percha swept across industry and manufacture; it was used as an insulator to cloth the underwater telegraph cables crossing the Atlantic.

It is not known where Leared sourced the gutta percha used in his stethoscope. The London Gutta Percha company placed an advertisement in the Great Exhibition catalogue listing articles displayed in the exhibition, ranging from waterproof soles for shoes and boots to ear cornets and trumpets to basins and bowls. They also mention a stethoscope and it is possible that this refers to Leared’s bi-aural instrument which he may have designed and asked them to manufacture. However, there was also a gutta percha shop in Wexford town, near to Oulart, in Ireland, where Leared was working as a doctor and he may have made use of this more local source of material.

Caroline Avery, whose doctoral thesis examines the uptake of mediate auscultation (the practice of listening to the body with the use of the stethoscope) by British practitioners between 1816 and 1850, argues that practical considerations such as affordability, portability and comfort motivated practitioners to make changes to the design of the stethoscope, rather than acoustic reasons.8There is no direct evidence as to precisely why Leared invented the double stethoscope in 1850 or 1851. A flexible stethoscope would, indeed, have been more comfortable for both the doctor and patient, however, in contrast to Avery’s thesis, Leared does mention acoustics and the ability to hear and distinguish ‘low sounds’.

In 1850 and 1851, Leared was practicing medicine in his home county of Wexford in the south east of Ireland. It is, perhaps, remarkable that he pursued his project of stethoscope redesign while working in a small rural fever hospital and dispensary surrounded by fear, poverty and famine.

Having re-designed the stethoscope, he was obviously convinced of its value. The mere act of exhibiting his stethoscope at the famous Great Exhibition should have placed it among the foremost inventions of the Victorian Age. However, five years after the Great Exhibition, in April 1856, James E. Pollock, assistant physician to the Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest wrote in the Lancet about a self-adjusting double stethoscope. Pollock gave priority of invention to two American doctors, Drs Marsh and Camman.

In August 1856, Arthur Leared responded to Pollock’s article claiming credit for having developed the double stethoscope first. He stated that his delayed response to the article was due to his absence from England during the Crimean War; he was employed in the English Civil Hospital in Smyrna at the time. ’To prove priority of invention is often a troublesome, and sometimes an unpleasant, task; but, in the present instance, the difficulty at least is not so great’, he suggested. Leared cited the description of his double stethoscope published in the 1851 Great exhibition catalogue and added that he had a double instrument constructed in 1850, if not earlier. Leared also insisted that not only was it possible, but perhaps highly likely, that his idea had been ‘pirated’ and the patent for it obtained on the other side of the Atlantic within the year. Leared was understandably bitter about his invention being so overlooked, and explained in a remarkably polite tone that he was ‘anxious to explain the matter fully now that, as a foreign importation, the double stethoscope had a fair chance of being tested.9

Pollock responded quickly to Leared, writing a robust response published in the next weekly issue of The Lancet, but which seemed designed to further annoy Leared.10 He accepted that he was not aware that Leared had exhibited a double instrument in the Great Exhibition. ‘The publication and exhibition of a stethoscope with two tubes in this country is undoubtedly due to Dr Leared; and it is certainly to be regretted that he did not bring it more immediately under the notice of the profession by having it manufactured and saleable, and so introducing it as a practicable and available instrument’. The accusations, counter-accusations and peevish comments in the continuing dialogue between Leared and Pollock were not untypical of medical discourse of the day. Having grudgingly granted Leared precedence, Pollock then cast doubt on the advantages of a double instrument. Leared was adamant that his invention was superior to the mono-aural instrument: ‘The double stethoscope, while inferior to the single one in point of convenience, certainly possesses the property of increasing sounds heard through it to a remarkable degree…as certain nebulae are resolved into stars by powerful telescopes, so specific chest sounds, obscure from their lowness, may be determined by the double stethoscope. I am sanguine, therefore, that the instrument will gain favour as a useful adjunct to our means of diagnosis’.11

In time, Leared was proved correct in his assessment of the superiority of the bi-aural instrument. In fact, bi-aural stethoscopes became the standard instruments used in clinical practice. The issue of inconvenience with respect to portability (the old rigid mono-aural stethoscopes fitted neatly into doctors’ hatbands while the new double stethoscopes did not fit easily into a hatband) was solved by doctors who put their new flexible stethoscopes in their pockets or wore them hanging around their necks. In any case, hats were to go out of fashion.

With passing decades, the double or bi-aural stethoscope worn visibly around the neck became the symbol of medical professionalism.12 Unfortunately, Leared did not patent, publicise or commercialise his invention however he was able to claim precedence. Writer Ian McEwan notes that to be first, to be original in science, ‘matters profoundly’. In his words, ‘to be for ever associated with a certain successful idea is a form of immortality’.13 While McEwan writes that who gets there first should hardly matter, in the realms of pure rationality and scientific advance, but such concerns have always made an enormous difference to innovative individuals such as Leared.14

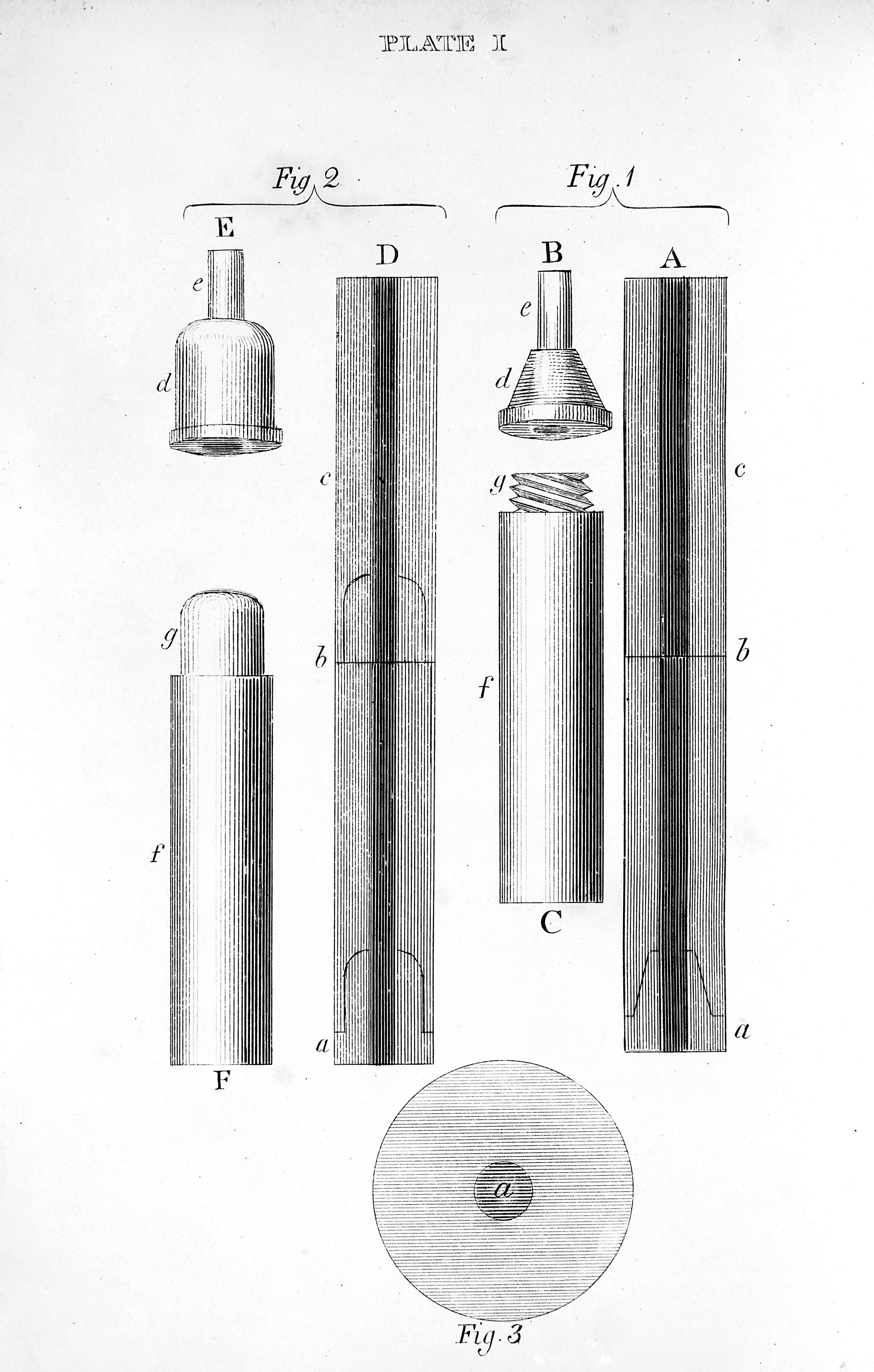

The last public sighting of Leared’s stethoscope appears to be a listing in the 1877 Catalogue of the Special Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus at South Kensington Museum; it does not appear to have made it into the London Science Museum collection after the exhibition.15 All that would seem to remain of his original stethoscope is a line drawing in an early medical textbook.

As for Arthur Leared himself, he moved to London where he had a very successful career as an elite hospital physician, spanning specialities such as gastro-enterology, cardiology and parasitology. He travelled widely and published medical and travel articles and books. His book entitled The Causes and Treatment of Imperfect Digestion ran to seven editions, with the final edition published posthumously.16

- Arthur Leared, ‘On the Self-Adjusting Double Stethoscope’, Lancet 2 (2 August 1856), p. 138. ↩︎

- National Museum of Ireland, ‘The Tara Brooch’, https://www.museum.ie/en-IE/Collections-Research/Collection/The-Treasury/Artefact/The-Tara-Brooch/4e7de8cc-9cf5-4352-a20a-34caf1bf4d95. ↩︎

- Anna Harris and Tom Rice, Stethoscope: The Making of an Icon (London: Reaktion Books, 2022), pp. 37-59. ↩︎

- Joel Stanley Reiser, Technological Medicine: The Changing Worlds of Doctors and Patients (Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 1-13. ↩︎

- Joel Stanley Reiser, Medicine and the Reign of Technology (Cambridge University Press, 1978), pp. 35-44. ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception (London: Routledge, 2003 [1963[); Adrian Wilson, ‘Porter vs Foucault on The Birth of the Clinic‘ in Roberta Bivins and John V. Pickstone (eds) Medicine, Madness and Social History (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). ↩︎

- John F. Fleetwood, The History of Medicine in Ireland (Dublin: The Skellig Press, 1983, p.132. ↩︎

- Caroline Louise Avery, Importing the Stethoscope: the Uptake of Mediate Auscultation by British Practitioners: 1816-1850. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Leeds, 2020. ↩︎

- Arthur Leared, ‘On the Self-Adjusting Double Stethoscope’, Lancet 2 (2 August 1856), p. 138. ↩︎

- James E. Pollock, The Double Self-Adjusting Stethoscope’, Lancet, 2 (9 August 1856), p. 175. ↩︎

- Arthur Leared, The Double Stethoscope’, Lancet, 2 (16 August 1856), p. 202. ↩︎

- Tom Rice, ‘The Hallmark of a Doctor’: The Stethoscope and the Making of Medical Identity, Journal of Material Culture, 15:3 (2010), pp. 287-301. ↩︎

- Ian McEwan, Science (New York, NY : Vintage, 2019), p. 48. ↩︎

- McEwan, Science, p. 42. ↩︎

- 3773a Original Double Stethoscope, invented by Arthur Leared, M.D. Dr. Burdon Sanderson, F.R.S*Catalogue of the Special Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus at the South Kensington Museum, London, Printed by G.E. Eyre and W. Spottiswoode, for H. M. Stationery Office; Correspondence between Anne Mac Lellan and Katie Daubin, the London Science Museum, May 2016. ↩︎

- Davis Coakley, Irish Masters of Medicine (Dublin: Town House, 1992), pp. 192-3. ↩︎

Anne Mac Lellan’s research interests include health, technology and medicine in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Anne graduated from the Centre for the History of Medicine in UCD in 2011 with a Wellcome Trust funded PhD. Anne has been a visiting lecturer at NCAD since 2011, where she teaches a module on the social history of medicine and medical devices. She is also a retired senior medical scientist who worked in microbiological surveillance. She is the biographer of Dorothy Stopford Price, who introduced BCG vaccination into Ireland and is currently researching and writing a biography of Dr Arthur Leared.